Alexandra Boutros

Wilfrid Laurier College

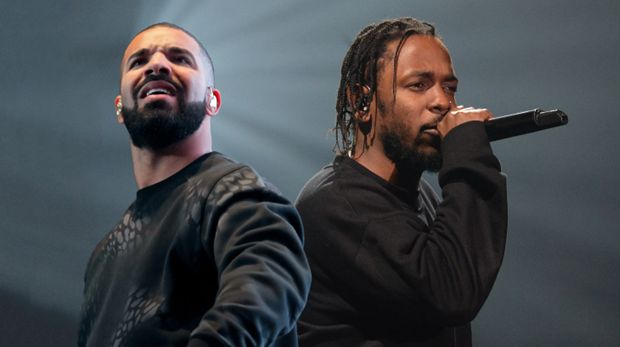

The epic beef between rappers Kendrick Lamar and Drake has as soon as once more demonstrated the linguistic acrobatics of rap tradition. The feud has seen each artists launch a number of tracks the place they lyrically diss one another. Beefs contain rappers disrespecting one another and might occur in diss tracks, but in addition by way of interviews, social media and different statements.

When Lamar viciously however masterfully raps about Drake “tryna to ring a bell and it’s most likely A minor,” he’s enjoying with language; utilizing double entendre and homonym (A minor being a musical chord and in addition a reference to an underage baby) to mix the literal, on-the-face-of-it that means of a phrase and its different potential meanings.

Some may lament the spurious info and salacious accusations flowing between Lamar and Drake. The artists might maintain lasting grudges in opposition to one another and the violent language of beefs can spill over into actual life.

Nevertheless, beefs are extra about self-conscious performs with language and that means than concerning the claims they make. They’re a testomony to the facility of language, utilizing hyperbole, irony and innuendo to finest insult one’s opponent. Beefs acknowledge the social energy of typically derided types of communication, like gossip and rumours.

Drake reminds us of this in one in all his responses to Lamar, The Coronary heart Half 6. The piece opens with a pattern of Aretha Franklin’s 1967 track Show It, whereas the one “proof” Drake presents for his personal claims is a coronary heart emoji on an Instagram publish.

Beefs are much less about fact claims and extra about showcasing talent and, simply as importantly, performing identification by way of language.

Identification in rap is tied to authenticity, the connection an artist makes to their very own autobiographical story and the way that story connects to different identities. Canadian-born, mixed-race (with a white mom and African American father), Jewish and terribly profitable, Drake’s authenticity is at all times challenged.

Critics took him to activity for Began from the Backside, arguing that his roots in Toronto’s prosperous Forest Hill (which Drake disputes) are hardly the underside. Critics have additionally argued that his delicate, “good man” persona obscures misogyny and sexism.

His sliding accents — a southern twang in Fancy, Jamaican patois in We Caa Accomplished and a Toronto accent in Canadian rapper Preme’s DnF — spawned accusations of cultural tourism.

Whereas such criticisms flow into on quite a few platforms, beefs typically goal Drake’s race. Lamar calls Drake “off-white” in his diss observe 6:16 in LA. Rapper Rick Ross simply calls him a “white boy” and in The Story of Adidon, Pusha T raps:

“Confused, at all times thought you weren’t Black sufficient

Afraid to develop it ’trigger your ‘fro wouldn’t nap sufficient.”

In his track Keep Schemin’ (Remix), American rapper Widespread says:

“You so Black and white, attempting to reside a n****’s life

I’m taking too lengthy with this newbie man

You ain’t moist no one, n****, you Canada dry.”

These traces emphasize how Drake is constructed as a Canadian who isn’t Black sufficient to say an genuine connection to African-American hip hop tradition. In Not Like Us Lamar means that Drake must mimic rappers like Future, Lil Child and 21 Savage to achieve “road cred.”

Claims of mimicry hang-out Canadian hip hop however have additionally seen pushback. In 1994, Canadian rapper Maestro Recent Wes launched the album, Naaah, Dis Child Can’t Be From Canada?!! that, within the phrases of Africana research professor Rinaldo Walcott, “targets the narrative of hip hop as an African-American invention,” disturbing the necessity for what he calls “mimetic identification” with america.

Lengthy earlier than Drake, Maestro produced Canadian raps difficult the concept that hip hop’s authenticity will depend on U.S. citizenship.

However Drake’s Canadian-ness intersects together with his mixed-race identification. The U.S. and Canada assemble Blackness in related, however unidentical, methods. Drake himself has prompt that emphasis on his whiteness is heightened in an American context: “That’s a really American factor … mild pores and skin and darkish pores and skin.”

When Black Canadians enter the U.S. public sphere, the place Blackness is seen in traditionally contingent methods, their very own lived expertise as Black Canadians could make performing Blackness in a U.S. context fraught.

The duvet of Pusha T’s The Story of Adidon is a photograph of Drake in blackface. It’s a surprising picture. Responding in an official assertion, quite than track, Drake defined that “This image is from 2007, a time in my life the place I used to be an actor and I used to be engaged on a mission that was about younger Black actors struggling to get roles, being stereotyped and typecast. The photographs represented how African Individuals had been as soon as wrongfully portrayed in leisure.”

Drake’s use of “African Individuals” in his assertion assumes an American viewers, erasing the specificity of Black Canadian experiences that, presumably, Drake was at the least partly trying to handle when he was nonetheless engaged on the Canadian manufacturing of Degrassi: The Subsequent Technology.

Whether or not blackface can ever be reclaimed as an anti-racist act (as Drake appears to counsel it could actually), it’s value noting that dominant narratives place blackface as American, despite the fact that minstrelsy was traditionally prevalent and widespread in Canada. This can be why Drake — Canadian and combined race — makes use of the time period African American, a reminder that Blackness itself is usually positioned outdoors Canada.

Canadian rappers who’ve gained fame each globally and inside Canada are sometimes linked to different nations. Ok’naan of Wavin’Flag fame was typically referred to by the media as Somali Canadian, Shad — host of Hip Hop Evolution — is recognized as Rwandan. Drake’s buddy Preme is famous to be of Guyanese descent, and even Scarborough-born Kardinal Offishall is recognized with Jamaica, the place his dad and mom immigrated from.

As a Black man, Drake doesn’t totally belong inside a nation at all times imagined as white, however neither does he totally belong to the imagined communities — immigrant or racialized — to which Canada expects Black people to belong. Absent cultural belonging to the state of his delivery, to the U.S. and its historical past of hip hop geography or to nodes within the Black diaspora, maybe it’s unsurprising that Drake adopts the sounds of others in a bid for hip hop authenticity.

Echoing Pusha T, Lamar says of Drake, “he lives inside confusion.” However arguably that “confusion” additionally lives outdoors of Drake. Drake, as advised by way of Widespread, Pusha T or Lamar’s beefy language, turns into an indication of an uneasy Blackness.

Not as a result of, as Pusha T claims, Drake himself is uncomfortable together with his personal Black identification, however as a result of these representations of Drake render Canadian Blackness and Canadian anti-Black racism invisible, even whereas suggesting that Drake isn’t fairly Black sufficient for hip hop.

Prof Alexandra Boutros is an Affiliate Professor in Communications Research at Wilfrid Laurier College. She is a daily contributor to The Dialog, a number one writer of research-based information and evaluation.